Improving global health requires transdisciplinary thinking and a focus not just on technologies but the systems that deliver them. Learning for Action in Policy Implementation and Health Systems (LAPIS) is a new initiative of DGH that works to foster better collaboration on health policy and systems issues across the UW and complement our strengths in specific disease areas with a look at cross-cutting topics, such as health financing and integrated primary health care.

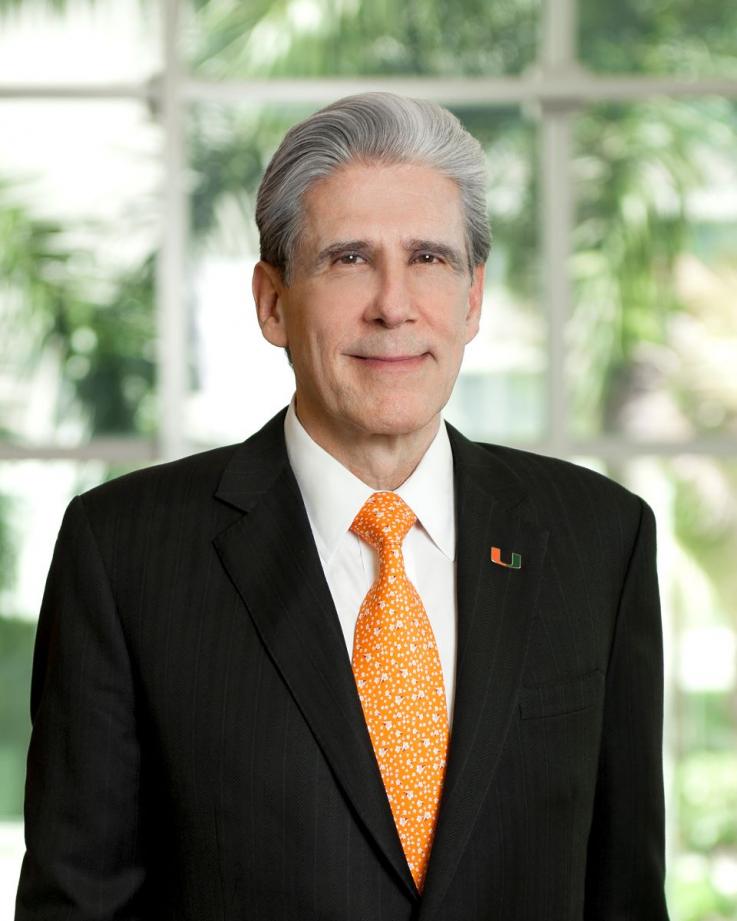

To help inform the Department of Global Health’s new strategy on health systems, LAPIS has organized a symposium to hear from UW researchers, practitioners, and local global health organizations about what they are doing on health systems and what they perceive as UW’s role in this field. Dr. Julio Frenk, MD, MPH, PhD, current President of the University of Miami and Former Minister of Health for Mexico, has been invited to give the keynote address at the LAPIS Symposium on June 16.

Dr. Frenk’s career has included leadership positions in all relevant aspects of public health and higher education: research, teaching, analysis of public policies, institution-building, international cooperation, and national public service. He is a fourth-generation physician whose paternal grandparents fled Germany in the early 1930s to build a new life in Mexico. Throughout his career and lifetime, he has catalyzed his deep gratitude for the kindness of strangers into a lifelong mission to improve the health, education, and well-being of people around the world.

We connected with keynote speaker Dr. Julio Frenk ahead of the symposium to learn more about his motivations for and interest in studying health systems, insights on the health policy world, and thoughts on decolonizing global health in conjunction with health systems strengthening.

How did you become interested in studying health systems? What experiences and role models were formative in your early career?

I grew up in a country, Mexico, which suffers from deep social inequalities. Since I was a young student, I began pondering what to do to ameliorate those inequalities.

When I was 16, I decided to spend the summer before my last year in high school living in a very poor indigenous community of the state of Chiapas in Southern Mexico.

During my time in Chiapas, I witnessed firsthand the shortcomings of health care in these communities. One day, while sitting in a health post, in came a very poor woman carrying her grandson in her arms. She had walked more than three hours to get this sick child to the town’s clinic. While traveling, she had injured her head, so when she arrived, she was covered in blood—in need of care for herself as well as her beloved grandchild. And there was no one. For me, this was the turning point. I remember thinking, “I am not only going to study these people, but I am also going to serve them.”

When I finished my basic medical studies and training, I decided that instead of following a clinical career, I would study public health. That way, I could deal not just with the consequences but also with the root causes of poverty and injustice underlying the plight of that poor woman and her grandson.

I went to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor to pursue a Ph.D. in public health, attracted by the luminous scholarship of one of the giants of health systems research, Avedis Donabedian, who became my mentor. He was a rigorous thinker and a pioneer in the conceptualization, measurement, and improvement of the quality of care.

While studying with him, I realized that clear thinking is a condition for effective action, hence the title of my upcoming lecture.

In addition to being a researcher, you’ve also served as a health minister. Are there one or two things that you think are important for academics to understand about the policy world, especially about how policymakers use research evidence?

After 25 years thinking and writing about complex health systems, I had the rare and precious opportunity of applying all I had learned. In the year 2000, at a historic juncture following the first fully democratic election in Mexico, I was appointed Secretary of Health of the Federal government.

One of the frameworks on which I based my work was developed by Harvard professor Michael Reich, a prominent pioneer of political analysis of health system reforms in developing countries, who proposed that public policies have three pillars: technical, ethical, and political.

If you have sound technical and ethical pillars, they will be powerful allies to build a political pillar. Politics here is not understood in its common transactional terms, often equated with “politicking,” but as a principled process for reaching agreement around shared social goals.

To do this, you must actively engage in the translation of research findings and technically worded evidence into the language of policymakers.

When I was appointed Minister of Health of Mexico, I used Reich’s framework to develop the national health policy document for the six-year presidential term, the title of which was “The democratization of health.” I also used it in the design and implementation of the comprehensive reform that was carried out then, whose main component was a public insurance scheme called Seguro Popular.

I was successful at translating the evidence that investment in a better health system would result in economic growth and help the overall economic goals of the country. It allowed me to persuade the minister of finance to support legislation that generated unprecedented levels of public investment in health with an explicit focus on advancing equity.

Recently, we’ve been talking more about decolonizing global health. Do you think this is in tension with concepts like health systems strengthening, capacity-building, and technical assistance? If so, what are a couple of concrete ways the global health community can begin to resolve these tensions?

A concrete way to resolve these tensions is to embrace a human rights framework. It is necessary to move from development aid, which fosters dependence, to international cooperation, which stimulates independence, to a higher state of global solidarity, which generates interdependence.

In a world marked not only by deep inequities but also by the acceptance of a set of universal human rights, global solidarity becomes the unifying force to redress those inequities and assure the realization of those rights.

A clearer understanding of the fundamentally interconnected nature of the health challenges faced by the global community requires moving beyond the narrow view of global health as the problems of the world’s poorest societies, to global health as the health of an interdependent global population.

Global Health Systems and Policy Implementation Symposium Series - Session 2

Join us to learn about work being done across DGH and network with other individuals focused on health systems and policy implementation.

EVENT DETAILS / ADD TO CALENDAR

WHEN: Friday, June 16, 2023, 12:30 – 6:30 p.m.

CAMPUS LOCATION: South Campus Center (SOCC)

CAMPUS ROOM: SOCC 316

Advance registration is required. Learn more about the event and register here.